Where Have All the Tomboys Gone?

The answer: It's complicated

A few months ago, a major media outlet for which I’d worked in the past (pre-truth-telling) approached me about a story. They were ready, finally, to tiptoe into the turbulent waters of gender, and wanted to do so by talking about tomboys. There were so many once upon the time! Where’d they all go?

I have a long and complex answer to that story—much more complex than the anti-gender identity ideology’s “all the tomboys are being transed” and not as simple as gender identity ideology proponents’ “no tomboys are being transed, only trans kids.” The editor asked that I do something I’ve never been asked to before, which is outline the entire story so the team could understand just what they were in for. I did so. And then they didn’t run it.

Below is a beefed up version of the outline of the story I’d hoped to write. It would have included multiple interviews with sociologists, historians, and psychologists. It’s long, but it’s important to make it to the end!

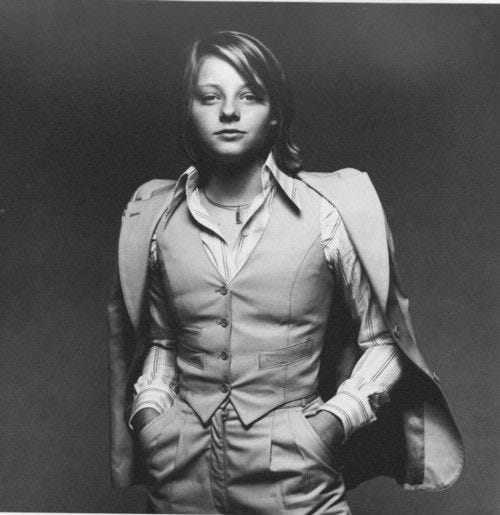

If you’re old enough, or a fan of vintage TV, you might remember the heroes—heroines, actually—of much of 70s and 80s TV. The tomboy, a tough-talking girl with a unisex haircut and a lot of attitude, was an iconic and common kid, in the media and in the mainstream of American life.

What happened to her? Why did she disappear? And why are trans kids, pretty much never heard of during the tomboy heyday, so common today? Are the trans kids of today the tomboys of yore?

The answer is complicated. The main reason the tomboy faded from public view is that we have generational gender zeitgeists. Childhood was heavily gendered in the 1950s (though tomboys were not so uncommon then as a category).

But by the 1970s, with the rise of feminism and of nonsexist parenting, that uniformity was replaced with a pediatric version of the gender revolution happening among adults (think David Bowie and Grace Jones, the elevation of androgyny and gender rebellion, the Peacock revolution). The tomboy became not just common but popular, promoted in the press and in the culture. Tomboys were, basically, cool, and so was the style associated with them. Thus, even nontomboyish girls like me had short hair and wore unisex clothes—which were, in actuality, boys’ clothes that girls could wear. Tomboyism was marketed, encouraged, as long as it would end at puberty.

But, aside from the gender-norm-busting album Free to Be You and Me, most of the tomboy-positive messages relied on rejecting femininity. There were boys’-to-girls’ size conversion charts in the boys’ section of the Sears catalogue, so girls could shop there, but no encouragement for boys to shop in the girls’ section. Thus, many of the kids raised as tomboys grew up to have kids and do the opposite, embracing femininity but rebranding it from weakness to strength. This became the era of girl power, of hyper-femininity being cool: Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Powerpuff Girls, Xena the Warrior Princess and Spice Girls.

This was the dawn of hypergendering, in which every aspect of childhood—clothes, colors, personality traits, toys—was gendered. In the early 2000s, when the Disney princess line entered the gendered consumer landscape, hypergendering was in our consciousness and our consumer psyche. By 2011, we had gender-reveal parties, celebrating the stereotypes associated with the sex of a baby before he or she was born.

So the first thing that happened to tomboys was: They went out of style. That means that the hypermasculine girl—sometimes called “always tomboys”—who had been provided cover under the tomboy umbrella, no longer had that refuge, that explanation. Extremely gender nonconforming kids have always existed, and seem to appear in many societies (though in societies where there are categories for them and an acknowledgement of the relationship between same-sex attraction and this nonconformity, there seems to be no gender dysphoria). The “sometimes tomboys” who might have played flag football but still worn a ponytail—she might have been able to assimilate into the next wave of gender culture by way of Sporty Spice. Sporty, feminine girls are still with us, they just aren’t dressing as masculine as they used to.

Not long after this generational reaction to hypergendered childhoods began, there was an increasing awareness about trans kids and a rather sudden exponential explosion in kids identifying this way. Partly what we’re seeing today is the generational reaction: Kids raised with hypergendering are rejecting the rigid gender roles and rules; from Girl Power to non-binary. One way to understand the explosion of non-binary identities is that they take on the best aspects of tomboyism—the release from gender stereotypes—without asserting that either masculinity or femininity is better.

But I think the main explanation is: Just as the vast majority of tomboy girls in the 70s and 80s were simply following fashion—they weren’t necessarily naturally gender nonconforming since it was conforming to have a boys’ haircut or wear Keds and tube socks—now it’s cool to be nonbinary, and fashion accounts for some of the increase. Some females who identify as nonbinary I interviewed only felt comfortable wearing pink after no longer identifying as a girl. It’s a way of rejecting gender stereotypes by way of rejecting one’s natal sex, which somehow gets you back to the openness of nonsexist parenting and Free to Be You and Me.

Another way of looking at it is that this generation of young people was raised so utterly baked in stereotypes that they believe that if they are not like a stereotypical girl, they are not a girl. The only release is through opting out of one’s sex category, and they have been taught that sex is a category one identifies into or out of. This means they believe that by changing names, pronouns, or categories, they are doing something revolutionary—but in fact, they end up reinforcing stereotypes, and making drastic changes to outrun them. It is social justice of the self, rather than an attempt to effect cultural change.

Still, this new zeitgeist provided a name for the always tomboy, a new way of understanding her (or him or them), and one that didn’t require she surrender her typically boyish ways at puberty. So, yes, some girls who would have been thought of as extreme tomboys when I was little would likely be thought of, or understand themselves as trans now. Some will be socially, and then probably medically transitioned, since what little research we have shows that social transition greatly increases that likelihood. When kids like this weren’t socially transitioned, they almost all outgrew their dysphoria and became comfortable with themselves during puberty (but some not until after).

In my limited experience, most girls who exhibited typically masculine behaviors in childhood were agitated and upset at the onset of puberty and wanted to socially and/or medically transition—but I’m not sure how much their families made room for gender nonconformity, or how much of a difference that makes when the messages that such behaviors make you a boy are so strong. However, there are kids who perform the gender roles of the opposite sex from a young age and have no questioning of gender identity and no dysphoria. Those seem to be the rarest of all.

I interviewed and surveyed dozens of former and current tomboys for my book and saw very few childhood differences between those who grew up to be lesbian and those who grew up to be trans—or neither—other than age and access to technology. That is, there was no way to tell who would persist or desist, but of course, few of the older women had had the option to transition, nor were there cultural messages celebrating and encouraging transition. Some adult women who were masculine girls, and who would have leapt at the chance to transition and are glad they didn’t, are concerned.

Lesbians United, a group that parked a #SaveTheTomboys truck around NYC, has been waging a campaign to wrest masculine girls from the clutches of an ideology that told them they were or might be boys because they were more male-typical than female-typical. I never talked to this group, but there is some research that shows tomboyish girls are more likely to grow up to be lesbians than non-tomboyish girls.

When I interviewed affirmative but nuanced clinicians (they exist! I promise!), they told me they weren’t as worried about the “always tomboy” types, the ones who’d been super masculine since childhood—presumably, they’d be less likely to regret (that leaves aside the important question of whether they would want to transition if we had room for gender nonconformity, but that’s for another time). The clinicians were far more worried about the almost-never-before-seen cohort of teens, mostly girls, arriving at clinics self-diagnosed with gender dysphoria and demanding medical intervention: the bulk of the 4000-5000% increase in trans kids. That means that the majority of girls with this condition, and likely undergoing transition, were not tomboyish. When you listen to stories of rapid-onset-gender-dysphoria girls, they are remarkably similar, right down to being properly feminine in childhood. Thus, dysphoria is also, to a certain extent, popular.

Have the tomboys disappeared? In many ways yes—some because they identify as trans these days, and some because it’s simply not a hip style for kids. There are masculine young women who transitioned and found solace, and there are masculine young women—and feminine young women!—who transitioned and realized they were lesbians (or straight) and wish they hadn’t changed themselves. Medical associations are not developing protocols to make sure people understand the relationship between gender and sexuality, or based on the very real premise that there is no way to tell who will persist or desist, be satisfied or regretful. Instead, the culture war continues, and it looks like this:

A good read. Thank you for this well written piece. I do wish it would be published more widely. IT is not confrontational or mean, but a good social science summary.

I'm of the Free to be generation. I adored Tatum O Neal. I wore blazers and had a Hamil wedge haircut, wore pants and blazers and strangers often thought I was a boy. Glad I had parents who encouraged my self expression. I am also glad that when I did go through puberty the 80's/Edwardian look was in. A high neck blouse, oversized blazer and drindl skirt helped me feel safe as I got use to my body changes and the icky feeling when someone who looks like your dad is whistling at you. It wasn't until I was in my 20's that I felt comfortable being a sexy, feminine person. Had I gotten the bombardment of messaging teens do now, supercharged with lockdown I bet I could have gotten caught up in the question of what gender I am? I wish technology had stalled at the Blackberry

As Lionel Shriver said in one of her essays, something like: I don't know what it feels like to be a woman I just am a woman. I understand that. I was lucky to grow up during the 60's with parents that liked sports and all those sports required strength and so that was a quality that was valued in our family for boys and girls. I didn't understand girly-girls. They were boring to me. They couldn't run fast and they didn't want to run fast. But I always liked boys so for me it wasn't a blossoming lesbianism but just a kid who loved nature and skiing and running and wearing my older brother's corduroys and hiking boots. That was considered 'cool' in my cohort. I don't understand why everyone wants to IDENTIFY as something. But I'm old and glad to be this age as I watch the madness unfold with the kids on social media and people thinking that it's okay for a biological man to identify as a woman and to race against women and if we don't agree with that insanity then we must be TERFS or TRANSPHOBES.

Nope.

We are not.

We are humanists and we are based in reality.

But thank goodness for you Lisa because your voice is so desperately needed here.

Your calm and your clarity.

The world needs your voice.