Guest Post: Elliot Page's Lesbian Memoir

A book review of PAGEBOY

I haven’t kept up much on Elliot Page. When I see photos of him, professing to reveal trans joy, I get the sense of a startled young man, teetering on the edge of sullen. When I read about his discomfort with the machinations of Hollywood, the makeup and glittery gowns, I think: What if he, and all the other starlets, took a seminar with Frances McDormand called, “You Don’t Have to Do the Bullshit,” in which they watched videos of shorthaired and makeup-less women strutting down the red carpet without giving a flying fuck. Cheaper and easier than top surgery!

My guest writer today, who also penned this wonderful piece on redefining the word “homosexual,” read Page’s new memoir, Pageboy, and has this review. The book’s title got me thinking about a theme that’s come up many times down here in the rabbit hole: how young girls want to be trans “guys”; they’re not thinking about becoming middle-aged trans men. What does it mean for Page leap from one category to another? What does it say about sexuality when sex is optional?

-LD

More below.

As soon as I open Pageboy, Elliot Page’s new memoir, the author objects to how I’m reading it. “[Q]ueer narratives are all too often picked apart or, worse, universalized—one person becomes a stand-in for all,” Page writes in the Author’s Note.

She is correct. I’m planning to analyze this trans memoir as if it’s a specimen. I’ve tried to understand trans identity in less creepy ways, but that’s proven difficult. Researchers haven’t identified a biomarker for it. Nor is there credible evidence that supports providing “gender affirming care” to gender dysphoric youth. When critics point that out, trans rights activists exhort them to scrap the search for objective evidence and instead “listen to trans voices.” So if I’m going to understand trans identity, I have to pick apart narratives like Page’s.

I want to understand trans identity because I’m a lesbian in my 30s and a lot of my peers, like Page, are coming out as male or nonbinary. This fascinates me. I’m inclined to think they’re chasing a trend, but I’m eager to gain a more generous perspective.

Page’s memoir helped a little. I came away believing she’s not a fool or a propagandist. I enjoyed the vivid, blunt style that prevails for much of the book. (I’m using Page’s preferred name but not her preferred pronouns. When it comes to how other people talk about us, I believe that we have jurisdiction over our names and nothing more.)

But Pageboy didn’t answer my number one question: what’s the difference between a transman and a lesbian?

The memoir covers Page’s life from childhood to the present. She grows up in Nova Scotia, her time split between a noble French-teacher mother and a charming, disappointing father. She begins acting professionally around middle school and has her big break at 20, when Juno premiers, in 2007. Page socializes with a lot of celebrities after that, but as for gossip, she only names the good guys and not the villains. Unease plagues her—“loneliness had always been a staple for me, an inherent disconnect from my surroundings”—but there is also joy. The story jumps around in time because “queerness is intrinsically nonlinear,” but the transition plot is mostly limited to the last 15% of the book.

Pageboy is basically a lesbian memoir. All its most credible, moving passages could have been written by a lesbian, but some of them have baffling trans content tacked on. For example, Page feels awkward on the high school party circuit, where "parents were at home, just respectfully tucked away." Wearing more feminine clothing wins her peers’ approval, but it's not a "magic fix" for her alienation. At school, one of "the hot girls" says to Page, "You have a nice ass." The girl "looks back, a covert smile, her hair following." I'm there. But then: "I wanted her to like his ass."

When I first read that line I puzzled over it, wondering why Page wanted to be addressed in the third person. Finally I realized she was trying to convey her ambivalent reaction to the compliment, and blaming it on the gender of her pants. It felt like a misdiagnosis. I think teenage Page wanted the hot girl’s compliment to be sexual but knew it probably wasn't. It was a gay problem, in other words, not a trans one.

Throughout Page’s life, her male friends are sweet and innocuous; her female friends are radiant, alpha, and in several cases, literal movie stars. As a lesbian, this schema is familiar to me, minus Catherine Keener and Olivia Thirlby. “A truly delightful human,” is how Page describes Max Minghella, her rival for Kate Mara’s affections. (Mara eventually dumps both of them.)

Some of Page’s alpha women are sinister. She miserably dates two sexual predators, including one who squeezes her throat “full throttle.” A third woman, a “world-renowned photographer,” unleashes at Page when Page can’t answer a makeup artist’s questions. “Do you even talk?” the photographer asks. She kicks Page’s chair. “Hard.”

Page is 5’1”, skinny, fine-featured and soft-spoken. She struggles with anxiety, anorexia, and a tendency to subordinate her needs to other people’s. One could argue Page is thus “feminine.” I thought about this every time I read about her getting manhandled, but she only mentions her small stature in passing. She says all her life people have seen her as masculine, a “dyke” or “that little guy.” I don’t doubt that straight people taunted her for seeming gay but I also suspect that gay people teased her for seeming femme. Honestly, it’s just what we do. I’m curious how she felt about butch/femme jokes over the years (they were mostly jokes for the millennials I crossed paths with, not serious identities, until gender ideology blew up) and how she has defined herself in relation to girlfriends, most of whom are probably taller and stronger than she is. But that’s not in the book.

Reviewing Pageboy in The New York Times, the trans journalist Gina Chua noted that “Page doesn’t really delve into questions of masculinity, or what it means to be a man[.]” Chua seems to accept this choice, but I see it as a fatal omission. Masculinity is hotly contested in the gender wars. Gender skeptics like me don’t think it means much at all; we expect men and women to follow the same rules and we associate a fixation on manhood with cheesy conservatives like Josh Hawley. Being a man must mean something to Page, since she believes she is one despite having a female body. But Pageboy doesn’t set forth her vision. For all I know, Page shares Hawley’s.

Her vision might have to do with clothes. She really hates feminine clothes, including “The way the tights glued to my body, the way my dresses flowed.” To be fair, she’s endured more sartorial abuse than I have because of her career. Most women in the US are allowed to wear pants to work; we don’t know the indignity of being forced, as an adult, to wear uncomfortable clothes that symbolize heterosexuality, especially ruffled evening gowns. Reading a paragraph by Page on the subject made me feel bad for her. Reading the millionth paragraph about clothing preferences made me want to kick her chair.

“I hated my swim suit. I loved swim shorts. Swim trunks, my dad would call them. The words, direct, with two syllables, roused elation in my mouth. Swim trunks. A satisfying crunch.”

Page announces to the world she’s gay at age 27. “After I came out, shockingly enough, the world did not end and my life improved, and now I had that as a reference in my chest pocket.” The episode triggers a period of “firsts and newfound boldness.” I know the feeling; I’ve never experienced a greater relief than coming out to my friends. Could Page – and other adult lesbians who come out as trans – be chasing that first high?

Page writes lucidly about sex, whether it’s getting fingered on a chair at a crowded party or sucking the “perfectly round and soft” breasts of the woman who is about to strangle her. In my favorite flex, Page confides that she remained so dry while attempting intercourse with her (sweet, innocuous) high school boyfriend that she visited a doctor to have her vagina examined. So I looked forward to reading what trans sex was like for her. Did she miss having sensation in her nipples, which a surgeon had “removed and slapped back on”? No comment. She rhapsodizes vaguely about post-transition sex, then claims her girlfriend’s “sweatpants and vintage T-shirt made me hard.”

As a young lesbian, Page deals with a steady stream of inane condescension. When she tells her mother she might be gay at 15, her mother responds, “That doesn’t exist!” After she comes out publicly, an unnamed “famous actor” berates her for seeking “attention” and threatens “I’m going to fuck you to make you realize you’re not gay.” Her manager warns her to “keep your personal life private” and claims she gives the same advice to straight clients. Page doesn’t condemn her mother or the manager, instead discussing their perspectives with nuance. But later, when people express skepticism that she is really a man, she responds with cliched, hyperbolic accusations that they are “denying my very existence.”

Page toys with trans identity for years but gets serious during the pandemic. In spring 2020 people mistake her for male when she wears a mask. She likes it. With no set to report to, she focuses on herself and decides to transition. (She is also separated from her spouse around this time; the narrative barely addresses her marriage or divorce.) The consultation with a surgeon “could not have been more chill. Nothing but smiles.”

Page undergoes the double mastectomy in November 2020, at age 33. Recovery takes a “couple months” and culminates in a “painful” appointment to remove drains from her chest and freeze the holes they left in her skin. She’s thrilled with the results. As for testosterone, Page writes basically nothing about its effects or her reasons for taking it (40 mg every Friday), except that her natural voice prevented her from passing as male.

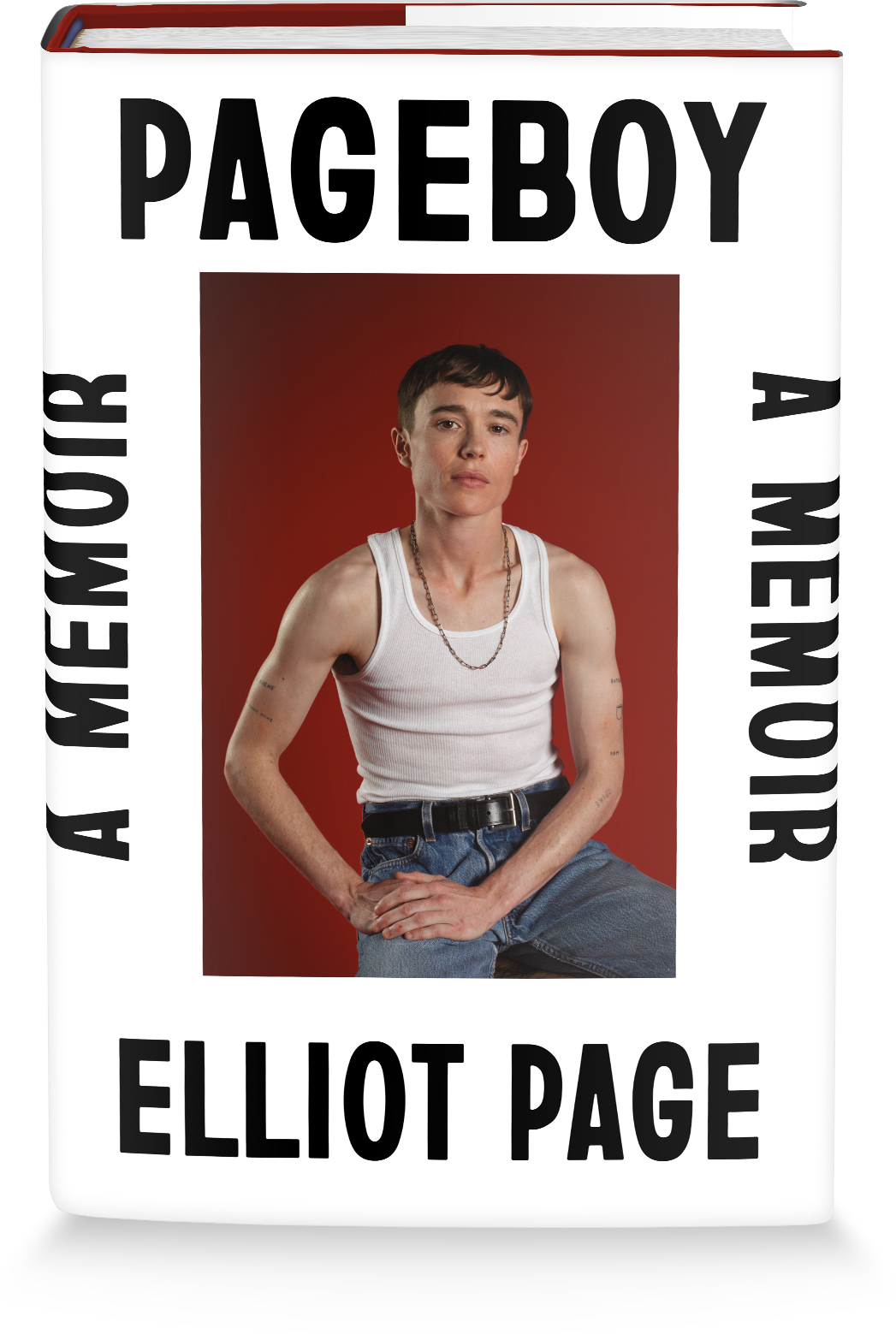

How does Page define her gender, precisely? The title of the memoir is "Pageboy," and she refers to herself throughout as a "boy" or "guy," not a “man.” At age 33, she catches her reflection in a mirror: “I saw the boy … the boy looked back at me.” The cover of the book features Page wearing a ribbed white tank top of the sort some people call a “wife beater.” It's an odd fashion choice for a 36-year-old man, but the look was de rigueur for lesbians in the 2000s when Page was, chronologically, a boi.

Eschewing femininity doesn't mean eschewing vanity. Many lesbians strive for a sporty teen-boy aesthetic while pretending that we work out to strengthen our mental health. (Yeah, the whole thing is weird.) Page mostly describes her physical transition goals in vague terms of self-actualization and joy, but an earthier motivation pokes through: “I had always worked hard on my core, and I wished its flatness would extend up the remainder of my torso.” Page is basically trying to achieve a type of lesbian hotness while announcing, in classic lesbian style, that she’s in it for her mental health.

Page says she’s happier now than she was before her medical transition began. “At last, I can sit with myself, in this body … my back straighter, my mind quieter.” I won’t pick that apart. But I won’t pretend to understand her trans identity, either.

Makes me want to cry that to be homosexual is still so difficult. We have come a long, long way in what is, in perspective, a short time. It is so joyful to be your authentic self. Please children-don't cut off your body parts because of homophobia. Seems like just another way of staying in the closet.

Interesting that Elliot "Boy" is a lot like with Dylan "girl".