The Question No One Is Asking

How does the hypergendering of childhood affect kids today?

Here’s how this whole thing began for me: At around age 4, my daughter started exhibiting stereotypically male preferences, wanting short hair and sweatpants and to play slightly more with boys than girls. There was no name for such a child by the early 2010s, and we wondered and, I’ll admit, worried, about her differences because there was no one to tell us what I now tell parents of gender nonconforming children when they query me: Congratulations! And: Nobody knows what it means about her future.

In first grade, she was given the word tomboy to describe herself by a fellow student, and that’s when I realized that most girls, even the super non-tomboyish me, had looked like her when I was a child.

That’s what eventually set me on the path to write a book about the science, psychology and history of tomboys and tomboyism. And in doing so I discovered that gender norms can shift generationally. Until about 1920, most young girls and boys were dressed similarly, in white dresses and with long hair, until they went to school around age 6. Toys and clothes were marketed by age, not sex. Even then, though, tomboys were popular characters in literature.

Only with an increasing understanding of homosexuality, and the assumption that it was the result of nurture, not nature, did the gendering of early childhood begin in earnest: Boys were raised as little men, girls as little women, to ensure they performed their proper gender roles, right down to being attracted to the opposite sex. It helped that the 1920s saw a growth of consumer culture and expansion of the publishing industries that could promote these ideas and make money off them.

But all the while, in books and later TV shows, there were popular characters called tomboys, girls with a temporary exit ramp out of girlhood, though all were expected to feminize come puberty. By the 1950s, gender roles for children were solidified, yet still tomboys remained as a viable exception.

Then, in the 1970s, those raised with the rigid gender of the 1950s procreated, and tomboys went from marginal to mainstream. During the feminist era, and the dawn of non-sexist parenting, girls were actively encouraged to pursue what was marked as “for boys.” A great example from Jo Paoletti’s book Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America: In the Sears catalog, there were boys’-to-girls’ size conversion charts in the boys’ section. Of course, no such chart appeared in the girls’ section, and there was no concerted effort to open girls’ worlds to boys. There never has been. The idea was to knock femininity for everyone.

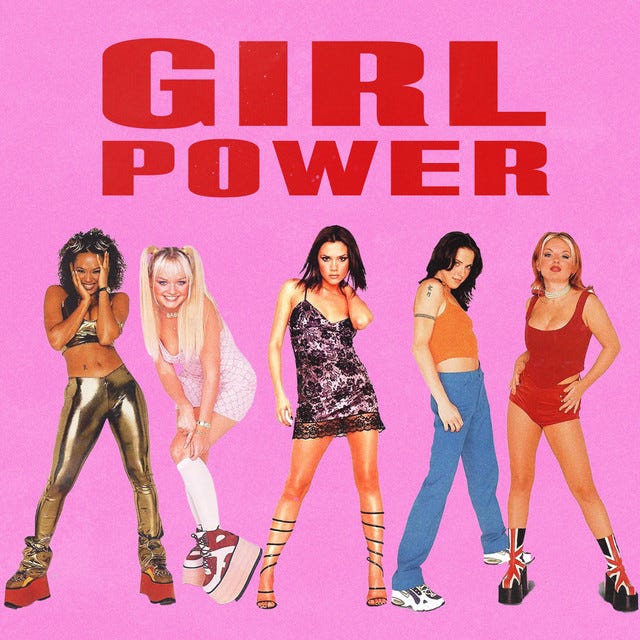

The tomboy heyday ended in a kind of backlash: the Girl Power era, in which femininity was power, but it emphasized appearance over action or strength. Some of those kids raised in the feminist era began to have kids, and reacted to their own gendered childhood experiences by embracing opposing messages.

By the 2000s, with regular prenatal sex testing and every possible item you could think of available in boys’ and girls’ versions, children began to be raised in the most hyper-gendered environment in history. Every color, toy, item of clothing, activity, proclivity, TV show, app—all divided into boy and girl versions, which often had explicit messages about who and how boys and girls are. Boys are smart, girls are vain, for instance. By 2011, we were celebrating the stereotypes affixed to our unborn children in gender reveal parties—and starting wildfires.

This happened to be around the time that gender identity ideology, and ideas about trans kids, were increasingly visible in our culture—perhaps itself a generational reaction to hyper-gendering, smashing the binary as a way to break free from these constructions and constrictions. Kids began to learn that gender was not a series of messages about who you were based on your sex—messages encoded in everything around you—but rather an internal sense of self. Few people seemed to understand that kids learn to master stereotypes by about age three, and will police one another to perform boy or girl right; this is often around when some organically gender nonconforming kids will emerge. It takes another five years or so for them to understand gender constancy, that your category is based on your body, not your adherence to stereotypes.

I have so far found no one asking questions about the psychological effect of hyper-gendering on children’s understandings of themselves—or even how these teachings about gender identity affect kids who don’t yet understand gender constancy. (Know of scholarly work on this? Please leave in comments! Meanwhile, read this piece, out this morning, on Common Sense about a school where some parents rejected these teachings and their kids were subsequently punished.) But I have found stories of detransitioners who had been unable, even as young adults, to discern the difference between sex and sex stereotypes.