One of the first voices I became intimately familiar with, after my parents’, was Mel Brooks’. That wasn’t just because his comedy album with Carl Reiner, The 2,000-Year-Old Man, was a family favorite, introducing me to lines (“I’d rather eat a rotten nectarine than a fine plum”) that have been branded into my brain.

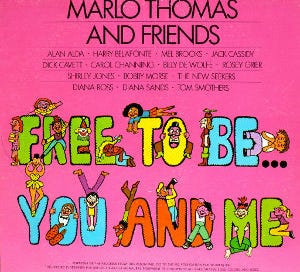

It was because we played Free to Be…You and Me, the seminal 1970s album about gender stereotypes, on repeat. I knew every line of every song and skit. I vowed I’d name my daughter Atalanta one day, after the track about the girl who runs as fast as the wind—and as fast as any man—in order to win the right not to marry. I learned that there is nothing wrong with boys liking dolls and that mommies can drive taxis or sing on TV.

And I learned, through Mel Brooks’ rounded Brooklyn vowels and Marlo Thomas’s signature rasp on the first track, “Boy Meets Girl,” that what makes a baby a boy or girl is not what they like or do but what kind of body they have—and that what kind of body they have doesn’t determine what they like or do.

Newborn Mel takes a look at himself in the hospital nursery and says, “Hmmm, cute feet, small, dainty…yep, yep! I’m a girl, that’s it! Girl time.” And he tells Marlo that she’s a boy because, “You’re bald as a ping-pong ball, are you bald.”

Marlo’s not so sure. She says she doesn’t feel like a boy, yet she wants to be a fireman when she grows up, while Mel wants to be a cocktail waitress. He must be a girl, he says, because he is girl-like: impatient, can’t keep secrets, afraid of mice. Marlo is none of those things—and also bald—so she must be a boy. To him, sex stereotypes and sex are inseparable.

Their conflict is resolved, the mystery solved, when the nurse arrives to change their diapers. He’s the boy because of what’s in said diaper, and she’s a girl because of what’s in hers. The message was clear: sex is real—and separates us from one another—but it doesn’t define who we are, our proclivities, our tendencies, our hair or our job choices or our fears. Sex is real; sex stereotypes are constructed, and need not limit us.

It is largely because of the influence of this album, I assume, that so many people of my generation believe that we have overcome gender stereotypes. Girls really can be anything they want to be! Look at the massive growth of women in medicine, women in sports, women in politics! (Boys? Too bad. You still have a narrow window of acceptable expression.)

But then we widen the lens, or maybe we zoom in, and see a different story. As teens, girls drop out of sports twice as much as boys do. Women have made massive gains in STEM but are still massively underrepresented. Only about a quarter of Congresspeople are women.

I’m sorry to report that not only do women and girls still have so far to go, but in fact, we are as beholden to stereotypes for both sexes as we ever were—just in a different, more insidious way.

We are living in an age of unprecedented hyper-gendering of childhood, in which almost every material aspect of a child’s life has a pink or blue version: pink and purple and pastel LEGO Friends for girls, which are essentially dolls and doll houses; bold-colored LEGO sets for boys, which are construction toys. Dolls and dollhouses help build nurturing and communication skills. Construction toys build spatial relations. Those are skills both sexes, and all kids, should have. Some boys’ clothes have slogans like “Unstoppable”; some girls’ have slogans like “Let’s stay home,” as this thread reveals. Gender-reveal parties celebrate the stereotypes associated with the yet-to-be-born baby. We are absolutely swimming in regressive notions about gender. Ideas that were exploded in the non-sexist parenting era of the 1970s have been pasted back together and packaged anew.

We have a novel way around those confines, though—a new method to accommodate children who are drawn to what’s outside the proscribed lines (even though all children were encouraged to venture outside those lines when I was young). Now many assume that when a girl is drawn to what’s associated with boys—rough and tumble play or short hair or boy LEGOs—she is a boy trapped in a girl’s body. I know this from personal experience—including the thoughts in my own head before I spent years researching gender nonconformity and realized that it is not predictive of any one outcome. Because of the gender lessons so currently in vogue, I had to learn all over again the most consistent lesson from my childhood: Biological sex is not destiny.

Yet others seem to believe that what we now call gender—a feeling inside someone of being boy or girl or neither—is destiny, and they assume they can forecast the future from a child’s nonconforming proclivities. What do we hear from parents of socially transitioned young females, living as trans boys? As one mom told People, “EJ was gravitating towards boys’ toys, like trucks, cars, dinosaurs and PAW Patrol” at a very young age. Then, around 2 ½, if you took EJ shopping, he always asked for the boy shirts,” she recalls. “At 3, in Target one day, EJ asked me if he was allowed to buy boys’ boxers. Once 3½-4 hit, EJ refused anything that was girly.”

In EJ and his mom’s world, sex is immaterial and gender is—literally—material. It can be worn like cloth. I fully support EJ reaching across the aisle to follow his heart’s desires. But the ideology that goes along with this child-rearing practice—that boy and girl are social, not biological, categories, which everyone must validate even if they don’t believe that, else they are bigoted—disrupts the fundamental message I learned as a kid. Based on the current cultural understanding of what it means to be a boy or a girl, the big reveal at the end of “Boy Meets Girl” is now moot. It doesn’t matter what’s in your diaper. If you’re afraid of mice and want to be a cocktail waitress, you are a girl. Marlo’s not a boy because her body is female but because, as she says, she doesn’t feel like one.

This can be hard to reconcile if the foundation of your worldview is the opposite of this zeitgeist. Being one sex and being drawn to the gender role of the opposite sex is normal. It’s what was encouraged when I was a kid. Now it has been turned into a kind of diagnosis that requires psychosocial and medical intervention, packaged as progress. Why does it feel so eerily regressive? I don’t find these messages to be supportive or understanding of gender nonconformity, the very thing I’ve now spent years trying to normalize. But I’m trying to move through a world in which my own reality has veered very far, apparently, from that of the readers of People. It is so disorienting. At least there are more lost souls wandering along with me, now.

I still play Free to Be…You and Me for my kids, because in my experience boys feel no safer playing with dolls now than they did when I was young, and girls, well, they still feel the pressures to be thin and pretty and nice. I still love the opening skit. Mel and Marlo still feel like members of my family, which was full of [atheist] Jews with New York accents. But I wonder how its messages can be assimilated into the world of gender my kids are learning. I don’t think we’ve fully metabolized the implications of shifting the meaning of the word gender from a set of expectations imposed onto kids because of their sex—which still happens—to a feeling inside them. How do they separate the feeling from the stereotypes?

Because I don’t see the genie of this idea going back in the bottle, I focus on how to accommodate it without surrendering my beliefs or my sanity (what little I had before I went down this gender rabbit hole, anyway). I have no answers. But I still have hope. My hope is that children learn to run as fast as the wind, and feel free to be themselves.

Your writing is so humane and kind. I just wanted to say how much I appreciated it in a time when a lot of us feel very torn in our feelings, and struggle to explain our concerns. All I want is for kids to grow up as I did, with a belief that - modulo biology - anyone can be any way they want.

I just can’t comprehend how so many people are so willingly going back to such regressive, narrow gender roles. It’s as if the “nice” adults have joined with the playground bullies in telling the gender nonconforming boy, “You’re not a real boy.”