“I know that there can be a lot of grief and pain surrounding childhood images,” the Facebook post read. “They can be painful to see but also painful to put away, so this is a way to save those cherished memories while also helping feelings of discomfort.”

And then it showed the handiwork of the company, Affirming Edits. In the “before” photo, a child—presumably a girl—wears a pink-striped jersey and her blond hair reaches toward her shoulders. In the “after” photo, the child wears a blue-striped jersey, and his hair has been photoshopped to just touch his ears—that is, to a length that many people in America believe is for boys.

One idea behind this near-literal erasing and redrawing of the past is to protect someone from the trauma of seeing themselves in their past identity—the identity imposed upon them by parents who ascribed pronouns, and all the cultural expectations associated with them. Changing their childhood photos reinforces the idea that the child was “born this way” and that he was never a girl. As one commenter put it, “To the people who say ‘it’s a lie’ or ‘you’re changing the past,’ that’s bullshit. He was always a boy. The presentation of a girl was the lie he had to live, until he didn’t. He was always a boy in that photo.”

It’s also valuable for trans people who are stealth, living their lives without other people knowing their biological sex or how they were raised. Many trans people just want to live in a way that’s most comfortable for them, and don’t want or need other people to know anything about their pasts. They don’t want to explain them, and they don’t want to reconcile them.

As Aaron Kimberly, a trans man and one founder of Canada’s Gender Dysphoria Alliance said in a video recently, trans folks often recast themselves as “I was a boy or girl all along” in conversation. “I would tell people that I played hockey instead of ringette,” he said. (Ringette, I subsequently learned, is to hockey as softball is to baseball.) Trans people are “always editing the details of our lives and it’s exhausting to have to do that all the time.” He likens it to being in the closet, having to hide parts of yourself, even if they’re your past self. Gender-affirming photos do the editing for you, literally and figuratively.

Experiencing a schism between how you see yourself and how the world sees you is very much the way we describe gender dysphoria, something painful and difficult to navigate. And yet, the way these photos are edited, the shift from pinks to blues, hearts to frogs, long hair to short, inadvertently does something far beyond rewriting one person’s past. They become cultural artifacts that reify the very stereotypes that people like me have spent years trying to dismantle. They navigate the cultural constructions of gender norms as if they are immutable, ignoring the very fact of their construction. Thus, they use the language of stereotypes to affirm identity, even if they don’t mean to.

This, I believe, is where things get sticky between *some* feminists and *some* trans people. For those women were raised to question stereotypes and to ask why there were a different set of rules for girls and for boys, some trans origin stories can be disconcerting. I’ve interviewed many trans men and non-binary folks who told me that their identities were revealed to them because they rejected pink and long hair and dresses; that’s how they knew they were different from girls, even though there is nothing inherently feminine about those things.

When I pressed them about this, they admitted that it was hard to explain. Their identities stemmed from about a deeply held sense of themselves, and our society was sufficiently limited in its understandings of gender that the only way they could explain it was to use the language of stereotypes. Plus, it doesn’t really matter what we put in the boy or girl category; most children will try to perform whatever stereotypes we associate with that category, so the rejection of them is not about the stereotype itself. It’s about rejecting the category.

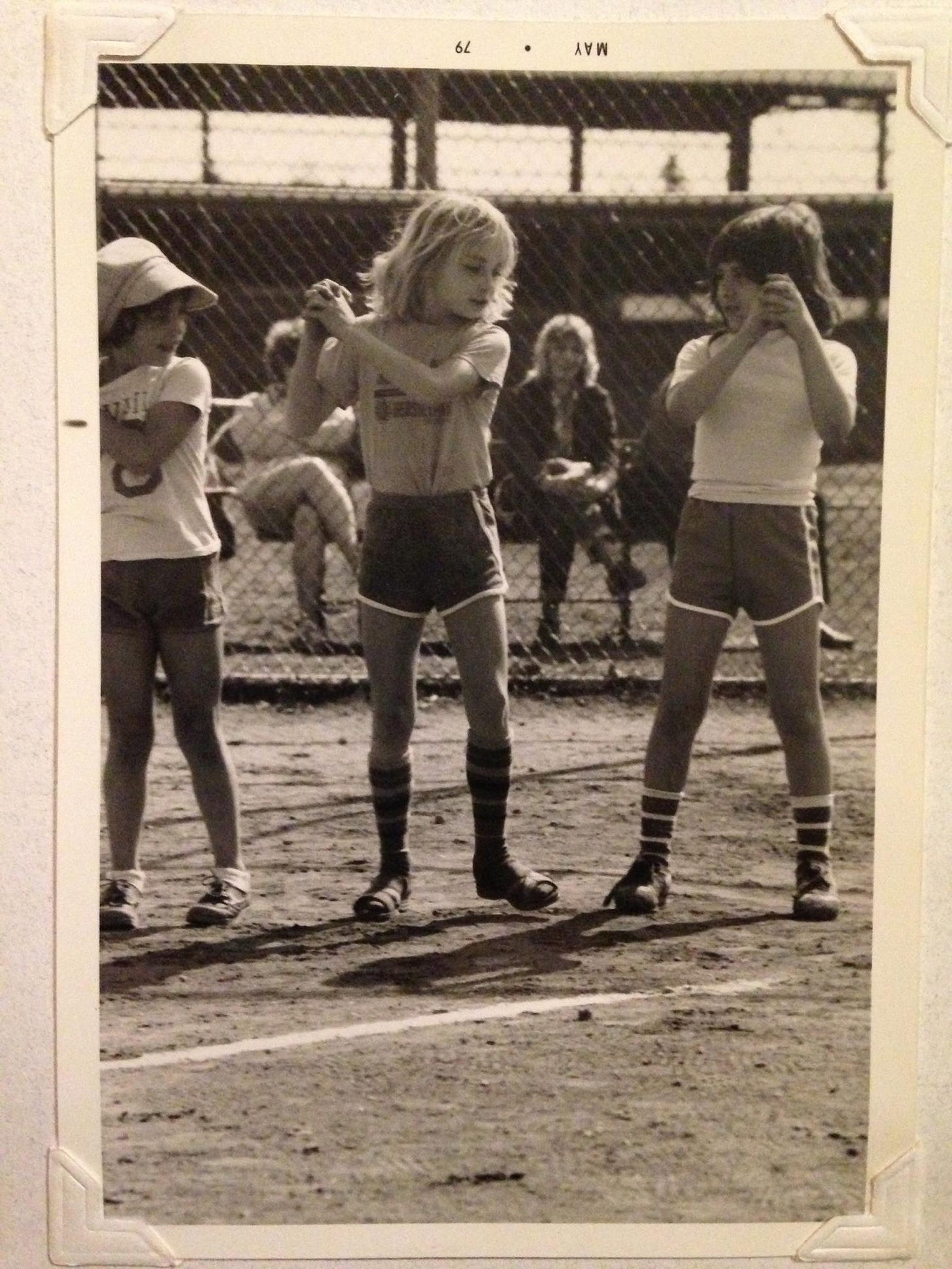

Still, it’s important to acknowledge that most of these stereotypical girl things are only recently designated as such, and have no biological connection to sex. Many of us raised in the tomboy heyday of the 1970s were encouraged to reject pink and long hair and dresses, to cross over the pink/blue divide into the land of boys. (For the record, I did not reject those things, but often even girls like me were wearing the same things as boys in the 70s; “unisex” clothes were the ticket, and they were mostly boys’ clothes that girls could wear. Plus: hand-me-downs).

That movement was codified in Title IX, which gave girls legal access to whatever boys already had in the field of education. Because before that, those rights were not guaranteed.

The idea that there should be separate haircuts or colors for girls’ or boys’ is fairly recent (it became more common starting about 100 years ago), and, if you haven’t already heard me yammering on about why, here’s the crib sheet: Once sexologists and psychologists started understanding sexuality as separate from sex at the turn of the 20th century (gender and gender identity were not yet concepts in the public mind), there was an increasing understanding of a homosexual as a type of person—not just a sense that someone occasionally behaved outside of the norm when it came to sex. And though at least one [gay] sexologist, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, argued that homosexuality was normal, ultimately it was seen as disordered. The way to discourage homosexuality was to emphasize sex differences early on, to teach little boys to grow up to be masculine, straight men, and to dress them as such. The reason we don’t dress little boys in pink or dresses? Straight-up homophobia.

The complication with making boy and girl social categories, instead of biological categories, is that doing so can rely on our social ideas and perceptions, and ultimately our stereotypes, reinforcing them instead of exploding them, which brings along with it the heavy baggage of sexism and homophobia. This is a tension I’ve come up against over and over as I’ve explored the history of gender and the gendered future we’re creating. One person’s liberation is another person’s oppression.

There are, of course, many trans people who don’t disavow their biological sex or hide their pasts. Buck Angel, for instance, explains himself as a female who masculinized his body to feel more comfortable. (Admittedly, many trans folks think of him as an apostate). That, he says, is what makes him trans, a prefix that means “across” and a word that inherently implies you’ve traveled away from your biological sex somehow. And plenty of people believe in affirming an individual’s gender identity without perpetuating cultural stereotypes. As one commenter on the Affirming Edits page put it, “I'm not here to say anyone who wants this service shouldn't absolutely use it. But maybe steer away from the bi-gendered marketing? The idea of ‘Boys have to be blue and Girls have to be pink’ isn't great.”

Over on Twitter, there were positive responses and objections, some politely pointing out the crystalizing of stereotypes, some spewing transphobic vitriol, others critiquing this practice as the ultimate snowplow parenting, encouraging fragility and perpetuating a kind of solipsism that chips away at any objective reality. (Affirming Edits’ founder, Rebecca Dayner, edited out the negative comments on Facebook—and there were plenty of supportive comments.) Some objections were from trans folks themselves who had painfully put away their past photos, but didn’t want to digitally paint a teacup blue because it communicated that boys could literally not touch a pink toy. But Dayner told me that not all people who engage her services choose this binary path. “I do work with people who are simply looking to move the images into a less binary representation of gender,” she wrote to me. The majority of people who get their photos edited are young adults or middle-aged folks, and most of the photos are from the 70s, 80s, and 90s, she said.

The fact that Dayner has a PhD in sincerity in visual art did not escape notice, either. I asked her to explain the PhD and its connection to this work. “Sincerity is a communicative phenomenon through which we convey or perceive someone’s authenticity,” she wrote. “In this way I do see the finished works as an act of sincerity. It is simply a way for people to reflect their authentic self.”

Stereotypes are often sincere. Most of us know they are not real but we affirm them, imbue them with meaning and then abide by that meaning as if it were fact. Dayner acknowledges that it’s important to look critically at gender stereotypes. However, she added, “If a person looks back on their childhood photos and feels deep pain or disconnection, then we need to respect their right to control their own image, and their choice to change it if that would lessen their hurt.”

As always, I come to the same conclusion, which is to make all colors, clothes, frogs, hearts, haircuts and teacups available to all children. Will someone transforming old photos to conform to culturally-created gender stereotypes—and lessen their hurt—interrupt this mission? I mean, no. But is there a way to create a world in which children don’t feel defined and limited by stereotypes, leading them or their parents to feel the need to edit their pasts to align with them?

I hope so. I don’t know how, but I hope so.

Next up, for paid subscribers: Getting de-platformed for liking a tweet.

Good stuff, Lisa! I hope we can get to a time when we can see, respect and acknowledge the human, regardless of what they are wearing