From the Rejection Archives #2: The Gender Unicorn

Somehow this mild op-ed was too hot for the media to handle

For the last year-and-a-half, I’ve been trying to publish pieces in the mainstream media about the problems with the current gender identity movement, its teachings, and its associated medical protocols—that is, I’ve tried to diversify the mainstream and liberal media narrative. From time to time I’ll share my failed attempts to do so.

What’s crazy about the unpublished piece below is: It’s really mild. I started sending it out in 2020, then revamped it and sent it out again in summer 2021, querying the usual suspects, many of whom I’d written for before: The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, NBC Think, etc. No dice. At this point, it probably feels outdated (and also, Zander Keig did an excellent video on this subject with FAIR). At the same time, I feel it’s important to show just how intense the censorship has become.

Today, for instance, NPR reported that a study showed 98% of kids who took puberty blockers went on to cross-sex hormones. They took this as confirmation that trans kids know themselves and regret is rare, rather than interviewing critics and concerned clinicians who might suggest that the majority of non-socially transitioned and non-medicated kids desisted. Reporters owe it to their readers to ask good questions, to employ skepticism, and to get their facts straight. And the media should publish more pieces that question the dominant gender paradigm. End of speech and onto the piece!

—LD

What’s missing from the Gender Unicorn?

As educators get ready for the new school year, in whatever form it’s taking, many are returning to the Gender Unicorn as inspiration for how to understand gender, and talk to kids about it.

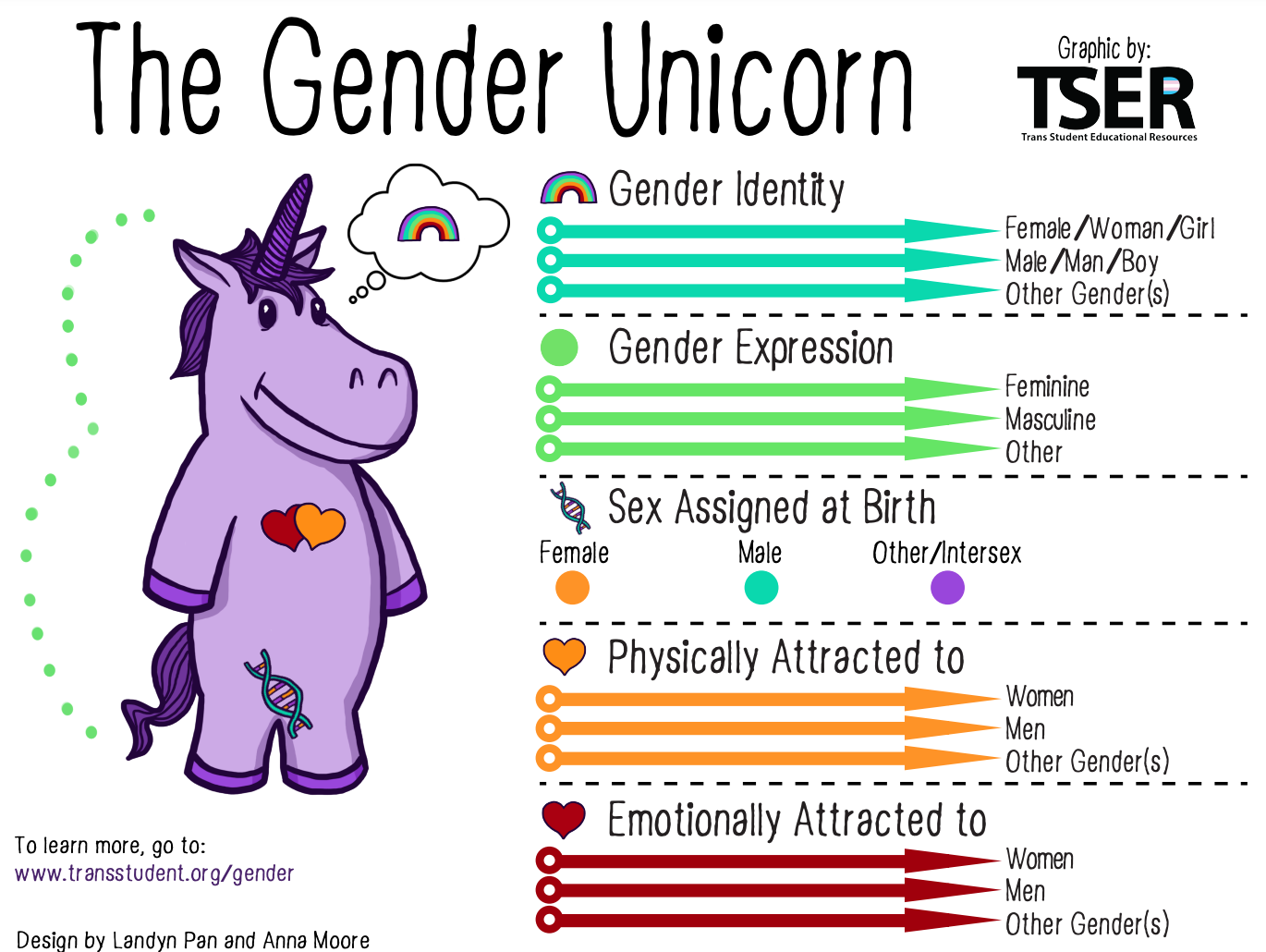

If you haven’t seen it, it’s a cute graphic of a purple unicorn displaying what are often thought of as the main aspects of gender. There’s gender identity (“female, woman, girl; male, man, boy or other”); gender expression (“feminine, masculine or other”); sex assigned at birth (“male, female, intersex”); and physical and emotional attraction (“to men, women, or other genders”).

The Gender Unicorn and its accompanying text, which has been translated into languages from German to Japanese, offers a valuable lesson to kids that each of us is a unicorn, possessing a unique gender combination. Your gender identity doesn’t determine your sexual attraction. Your sexual attraction doesn’t determine your gender expression.

It’s also ignoring what is, to me, the most important aspect of gender that kids, and grownups, need to understand and discuss: gender stereotypes.

Research shows that children as young as two years old can understand their sex category, and that by age three they’ve mastered the stereotypes associated with them. They know what clothes, toys, colors, and personality traits are supposed to go with each sex. Kids who once played together often begin to segregate into boy and girl groups then, and learn to police each other for not performing their gender roles correctly, for not playing the right way, or with the right people or things, or wearing the wrong stuff. By the time they’re in preschool, kids are learning—falsely, and deeply—that the whole world is divided into pink and blue, and that they should stay on their side of the line.

But look at what’s on either side. There are boy and girl LEGOs, which develop different skill sets: spatial relations in boys; communication in girls. Pink and blue bikes, computer tablets, games, apps, pens, toy ovens, candy, bibs, sneakers—often without much in the way of treads for girls, making it harder to climb. With all those unnecessarily gendered products come our ideas about what kids should be like, what they should do, who they should be. There are pink and blue activities, like ballet and baseball. And pink and blue personality traits: girls are sweet and sedentary and like hearts and rainbows; boys are tough and sporty and don’t cry.

This unprecedented hyper-gendering of children’s material and psychic worlds is the reason we have to have discussions about the plagues of girls’ low self-esteem and eating disorders, and boys’ toxic masculinity. A third of boys feel pressure to be violent, to hide their emotions and to insult girls, or talk about them as sexual objects, according to a 2018 report, The State of Gender Equality. Most of them learned that “acting like a girl” was an insult, hurled at them when they expressed any emotion other than anger.

Meanwhile, many girls who’ve spent their preschool years fully clad in princess costumes often go through what psychologists call a “pink-frilly-dress-to-tomboy phenomenon,” around age six, suddenly declaring their hatred of pink and dresses and opting for sportier clothes. This is not just because of their evolving understanding that sex and gender stereotypes aren’t married—that what you wear or who you play with doesn’t determine your sex category. It’s because they understand that what’s culturally marked as feminine is less valuable in our society than what’s thought of as masculine. They’re internalizing sexism, and the message to devalue what’s feminine—by age six. So are boys.

But things seen as feminine, like communication skills or kindness or dolls, are actually just human traits and toys. By the late 19th century, baseball was a common pastime for girls, and 82% of boys played with dolls. They still do—we just call them action figures. Things seen as masculine, like physical activity and leadership, are just human. If kids don’t learn early and often to reject stereotypes, they are bound to be limited in their career choices, in their tolerance for gender diversity, in their own self-acceptance and humanity.

It wasn’t always this way. A hundred years ago, both boys and girls often wore long hair and dresses in early childhood, because adults wanted to de-emphasize their sex; that was associated with sexuality, and adulthood. But that changed when sexologists and psychologists started seeing homosexuality as a classification, a kind of person not a behavior. Thinking nurture, not nature, caused homosexuality, child psychologists encouraged parents to dress sons as little men, to give them toys that emphasized their gender roles, so they wouldn’t embrace the feminine—so they wouldn’t turn out gay. Now, every single part of childhood is pink or blue—even though pink used to be considered masculine, since it’s a variant of red, and blue was feminine, associated in its lightened form with the Virgin Mary.

It changed once, and we can change it again. It turns out it’s not that hard to counteract gender stereotypes. As one study put it, showing kids “counter-stereotypical pictures is a valuable strategy for overcoming spontaneous gender stereotype biases”—they’ll believe a toy is for a boy or girl if you show them images as such. Same with exposure to counter-stereotypical career role models, which can affect what careers they aspire to.

The language around gender is fraught. We can and should find ways to talk about this complicated subject, starting with very young children. But let’s include our cultural norms, expectations and stereotypes when talking about gender. Let’s add that layer onto the unicorn, and weave it into discussions with kids and educators. Whatever their gender identities or expressions or sexual orientations, kids are all being deeply affected by gender stereotypes.

It’s just infuriating that this can’t get published in the mainstream media. How is ANYTHING you wrote here controversial? (And even if it were, that shouldn’t disqualify it from publication!) How are people not recognizing how regressive gender ideology really is?

It kills me that 15, even 10, years ago, this would have been considered left/progressive. Now it's...fascist? I've been off social media for months (for my mental health), but every once in a while I think about what would happen if I shared something like this. 99% of my friends are leftie, but I bet many of them would get in touch secretly and tell me they agree. My biggest worry is my kid getting wind of it, and running away. Thank you, as always, Lisa. You keep me going. xo